Back in 2016, a then-new literary health and wellness publication, originally called Issues but later called ENDPAIN, commissioned me to write for them about grief. I think this was my first-ever commission, and I got it because the editor was friends with one of my MFA pals. I proposed to write about something that was causing me pain and grief back then, something I had been thinking about for a while at the time: the deluge of Mother’s Day marketing emails hitting my inbox, reminding me that my own mother was dead. The marketing emails were particularly bad that year, I think, and they invaded my space more than greeting card displays at drugstores ever could, because they appeared on my phone at all times of day and night, wherever I was.

That publication no longer exists, and now there is new ~discourse~ around those marketing emails. In the past year or two, in the month leading up to Mother’s Day, some brands (but far from most) have sent a different kind of email, acknowledging that the day is hard for a lot of us and offering the opportunity to opt-out of related marketing messages. These days I just delete every Mother’s Day ad I get, and they don’t bother me as much, mostly because I exorcised my feelings about them in writing. But I still opted out every chance I got, because I don’t need a reminder to book a facial for my dead mom anyway.

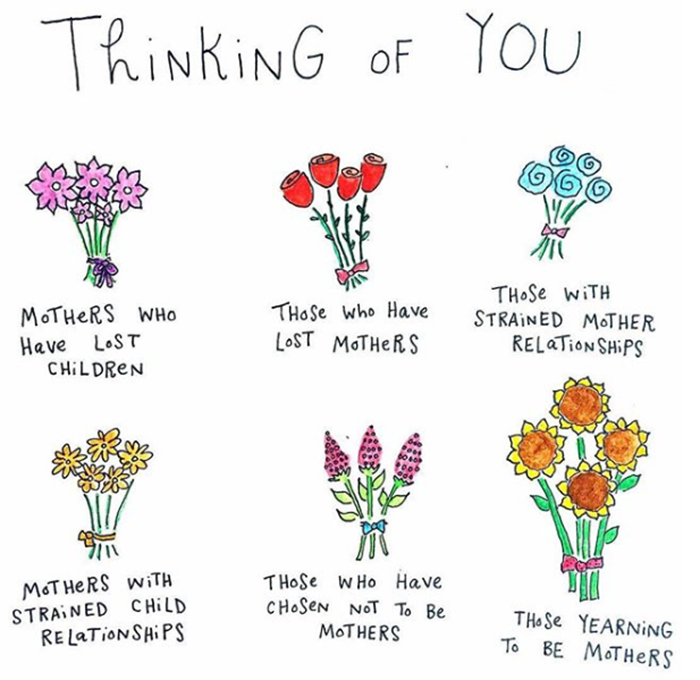

Discourse-wise, I’ve seen commentary on Twitter and Substack that these brand emails and Instagram reposts of Mari Andrews’s “Thinking of You” illustration show that we don’t know how to talk to one another about Mother’s Day. True, the brands are being cynical and self-serving, and the impulse to acknowledge that other people might be having a rough time on Mother’s Day after you post a cute picture of your own mother declaring her the best ever might come from the same place. But I think that all this discomfort can also point us to another possibility—one where we examine why we’re even “celebrating” Mother’s Day in the first place, and question if the (largely consumerist) expectations around the day really serve anyone.

At any rate, I don’t think it’s a bad thing to be reminded of other people’s potential pain and discomfort, even if it interrupts your brunch. Here’s that old essay—I’d write it differently now, but it still feels worth sharing, especially since it’s otherwise lost to the internet.

Don’t Forget

When I was growing up in a middle-class town on Long Island in the 1990s, we didn’t much celebrate Mother’s Day and Father’s Day. There were no brunches, no breakfasts in bed, no family gatherings. It wasn’t just that “brunch” wasn’t part of the vernacular of West Hempstead back then—my parents were never the kind for celebrating anything other than major holidays (Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter) and my brother’s and my birthdays. They never wanted celebratory attention turned onto themselves.

Dad was a Classics-scholar-turned-NYPD-lieutenant, a boy from Flatbush, Brooklyn who translated the New Testament into Greek in his spare time. He also coached my brother’s Little League teams and kept impeccable stats books of each game, each RBI. He was, at once, a man who fully embraced suburban fatherhood and who etched a space for himself outside of it. I think he’d be pleased to know that I think of him as sui generis.

Mom, on the other hand, was fully of the Long Island community we lived in—at least on the surface. She had grown up in the very house that my brother and I were raised in, had attended the same elementary school and high school we would attend. She was a PTA president and a Daisy Girl Scout troop leader and a Cub Scout den mom. But she was also older than the other PTA moms, and she distanced herself from the suburban housewife image by being the kind of woman who always wore jeans and loose Oxford shirts, the kind of woman who smoked Marlboro Reds. She was sui generis, too.

Though my parents didn’t like to draw attention to themselves, they did everything they could to support my brother John and me, down to praising the handmade gifts we would give them for Mother’s Day and Father’s Day—the one way we would mark those holidays. In kindergarten, my class cut out circles from fluorescent orange card stock, glued them to popsicle sticks, and wrote “My Pop is Tops!” in shaky five-year-old hand. I also recall making marker-decorated keychains and tissue-paper-decoupaged heart magnets. Desk supply holders were fashioned out of Maxwell House coffee cans covered with construction paper and decorated with poorly drawn hearts. Every single one of the crafts featured a wallet-sized school portrait, pasted smack in the center. My parents had two sets of these crafts—John made his own versions three years before me—and proudly used and displayed them all.

Too soon, all of those crafts began to appear not just as symbols of both our love for our parents and our parents’ love of us (they really had to love us to display our elementary efforts at artwork), but as painful reminders of loss. Too soon, my parents were gone, dead one after the other; Mom of lung cancer in 2002, Dad of prostate cancer in 2004. When Mom died, I was 12, John 15; when Dad died, I was 14, John 17. Mom’s cancer diagnosis, decay and death happened quickly, within a span of four months. Dad’s cancer had been in remission until Mom’s diagnosis, but when Mom got sick, Dad got sick again, too, and his cancer spread until he died exactly two years and two weeks after Mom.

After Mom’s death, I tried as hard as I could to disassociate from the fact of my loss, in part because it made me so different from my friends and the people in our community. That our elementary school teachers had us make crafts for Mother’s Day and Father’s Day made clear that this was a place where the nuclear family was still largely intact. None of my friends when I was growing up had divorced parents, let alone dead parents. I wanted to pretend that everything was okay, that nothing had changed, that I was still normal, because it hurt too much to look head-on at how much had changed.

Of course, all of my attempts to push my grief away were for naught. Everything reminded me of my mom—those leftover gifts weren’t my only triggers. I was mostly able to avoid having to bring up the fact of my loss in conversation because the people around me—my friends, teachers, classmates—knew that my mom was dead and knew that I didn’t want to talk about it. But about a year and a half after my mom died, when Dad was still alive (though very ill), my ninth grade English teacher assigned a project loosely based on John Steinbeck’s The Pearl that seemed cruelly tone deaf to my situation.

Throughout The Pearl, the protagonist pearl-diver, Kino, hears different songs in his head, the most memorable of which being “Song of the Family”; our teacher asked us to each choose our own song of the family and create a poster board with pictures of our families in order to present on our relationships. Even as a 14-year-old, I knew that this project lacked pedagogical merit (what were we meant to learn about literature from this?). I was hurt that my teacher, who knew of my situation, assumed that I would be comfortable with discussing my mom’s death and my dad’s rapidly deteriorating health in front of the class. In the end, I excluded my mom from my presentation and spoke about my dad as though he were healthy—it was the only way I could make it through the project without bursting into tears. On my poster board, the only picture of my parents together was from their wedding day in 1985, standing outside of a church, their eyes crinkly with joy. I no longer remember exactly what song I chose as my “Song of the Family,” but it was undoubtedly something upbeat that masked my grief and my anxiety over my father’s metastasizing cancer.

The more I thought about this project, the more I realized that it wasn’t just tone deaf to me, but to any of my other classmates who didn’t have an ideal home life—what about those of us whose parents fought bitterly or who felt like we were misunderstood? It would have been impossible for any of us to be truly honest. How could anyone choose anything other than a happy song? It was clear that we were meant to brag, to be beacons of white bread middle-class family life. To do otherwise was to admit that we deviated from some supposed norm. And while my teacher wasn’t wrong that most of us had two living and married and loving parents that we could talk about for this project—that was a norm—she had neglected to empathize with those of us for whom merely hearing the highlights reel of other people’s home lives could be a difficult reminder of all the ways our own lives failed to stack up, all the things that we had lost or never had to begin with.

After Dad died, I grew even more sensitive to assumptions that everyone has parents who are alive. Each spring when I was a teenager, I resented the Hallmark Mother’s and Father’s Day card displays at CVS and the department store sale circulars telling me to buy jewelry for Mom and golf shirts for Dad, because it felt to me that they were rubbing my face in what I didn’t have and everyone else did. I resented that I had to mark two extra days on my calendar of grief, two extra days outside of my parents’ birthdays and death days where my mind would slip into a vortex of sorrow that felt impossible to claw my way out of.

Still, for the first few years of parentless Mother’s and Father’s Days, it was easy enough for those two extra days to remain circumscribed into 24 hours each. Even when my brother and I moved away from Long Island the summer after Dad died to live with his sister in New Jersey, and I no longer had the benefit of the people around me knowing that my parents were dead, I still was able to numb my brain when people talked of Mother’s and Father’s Day gifts and celebrations. In the early 2000s, marketing for these holidays was still mostly limited to catalogs and greeting card displays, and maybe some window decorations in the mall. But now, with endless email marketing, the barrage of Mother’s and Father’s Day reminders—of reminders of my loss—lasts all spring.

My relationship to my grief has changed over time—it no longer hurts me so much to acknowledge that my parents are dead, to talk about them, and to hear other people talk about their relationships with their parents, be they good or bad. That I write about my parents now is the truest proof that my loss is no longer too raw to touch. But the sheer volume of emails I receive leading up to Mother’s Day and Father’s Day can cause me to slip back into my teenaged resentment and sensitivity.

Starting in April, my inbox gets crammed with marketing emails that implore me to “Give Mom breakfast in bed” (from Seamless), say “For all you do, thanks Mom” with a new pair of shoes (from DSW), rent a designer dress for mom (from Rent the Runway) because “she always made you feel beautiful, now it’s your turn.” Father’s Day emails are no better: Etsy tells me weeks in advance of the third Sunday in June that “it’s never too early to shop for Dad,” and OpenTable asks, “How are you celebrating Father’s Day?”

I am mostly able to brush these messages off, to immediately click “delete,” but sometimes they fly into my inbox on days when my grief is sharp, when I miss my parents and wonder what life would be like if they were still around. Would my mom, who loved shopping at Lord & Taylor, ever be interested in renting a dress from Rent the Runway? Would my dad trawl Etsy for Beatles paraphernalia? Would all of these marketing emails be missing the mark anyway, trying to sell me on buying gifts for the stereotypical mom (she loves scented lotion and perfume and gardening tools!) or dad (he loves shaving supplies and golf clubs and power tools!) that my parents would have actually hated?

Over the past few years, the effect these marketing emails have on me has been compounded by social media posts that acquaintances make about their parents on Mother’s Day and Father’s Day. It’s become de rigueur on Facebook and Instagram to post a picture of your mom on Mother’s Day or dad on Father’s Day. One of my friends told me that beyond just a card or a gift or even a day spent together, her mom expects a public Facebook declaration. These posts have become overwhelming to the point that I have effectively quarantined myself from social media on these holidays, because my feeds can seem like wall-to-wall reminders of what I’ve lost.

But even while I can succumb to waves of grief and discontent on Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, I am thankful for the community of friends I have who have also lost a parent, who check in on each other just to say “thinking of you” on these days. I no longer feel like an anomaly. There is comfort in knowing that although everyone’s grief is different, we all grieve. And in a strange way, there is comfort in knowing that although my parents are gone, memories of them can still flood me whenever I receive a silly marketing email, even if that flood of memories hurts.